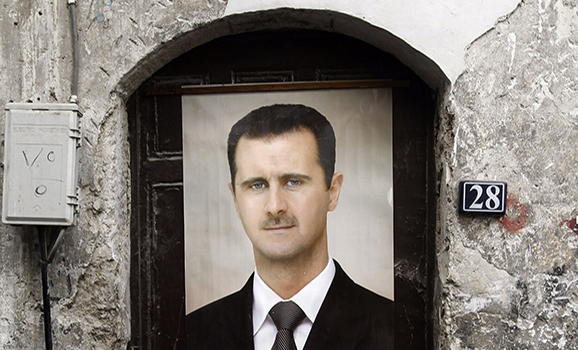

How Lucky Is Syria’s President?

By: Ali Hashem for Al-Monitor Lebanon Pulse Posted on September 12.

Bashar al-Assad may be the luckiest man in the Middle East, and maybe in the world. The defiant Syrian president has been under fierce popular, military, regional and global pressure to step down, his country is almost destroyed, more than one hundred thousand of his people have been killed and thousands of his soldiers splintered. Yet he is seriously considering running in the 2014 presidential election.

Assad is neither detached from reality nor delusional. The man knows well that he’s backed by a solid front that he can bet on. Assad’s front is ready to do whatever appropriate to keep him in power, providing money, arms, political backing and fighters.

Iran, Russia and Hezbollah each in their own way are fighting an existential battle along with their ally. The Russians are battling for their last base on the Mediterranean Sea, and for their gas pipelines in Europe that they fear will be replaced by Qatar’s if Syria’s regime is toppled. A Russian diplomat once said that there are plans to build a gas pipeline from the Gulf to Turkey that would traverse Syria to the Mediterranean, with the gas then being shipped to Europe. Such a project would mean the end to Russia’s upper hand in the European energy sector, and this means a lot in politics, and on the economics side.

As for Iran, Syria signifies the western borders of the Islamic Republic’s national security. Syria is the forefront of the “resistance bloc,” as moderate president Hassan Rouhani put it. Damascus is Tehran’s closest ally since the ’80s; together they have formed an alliance that has included Hezbollah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad and other groups fighting Israel. Iran and Syria were also together in Iraq, in the same bunker in the standoff in Lebanon after the assassination of former Premier Rafik Hariri and now they are tied together in the ongoing war in Syria.

Both Iran and Russia share borders with other parts of the world, so despite any harm that might happen if the regime in Damascus falls, they can still survive within their borders. While later on they perhaps might find other ways to enhance their policies in the region via new allies, Hezbollah cannot. The Lebanese group isn’t ideologically linked to the Syrian regime — Hezbollah members are Islamists, while the ruling Baath Party is secular — and perhaps it is important to mention that in the ’80s the Syrian army, when it was in Lebanon, killed dozens of Hezbollah fighters in what is known as the Massacre of Fathallah. The fighters were killed because of Hezbollah’s support of the Palestinian factions in Beirut when they clashed with the Syrians and their allies. But Hezbollah today breathes through Syria: Its weapons have only one route — via Syria — and if Syria’s regime falls, then Hezbollah knows well that a long war with Israel might put an end to its military power and power to influence. Moreover, it would be the beginning of the end with all the hostility surrounding the party in the region — hostility that existed even before the start of the Syrian crisis — because of sectarian strife.

Assad is Syria’s lucky man, because he knows that he is vital for all his allies, united behind him and beside him, each in their own way. Hence they all complete each other, and show that any real battle to uproot his regime might turn the whole region into a barrel of dynamite.

On the contrary, Assad’s foes aren’t united, and neither are their allies. The opposition alone is made up of dozens of groups, from different backgrounds, backed by different, contradictory powers that can talk for years but, when it comes to action, are masters of the art of escape. Assad is lucky to have such an opposition backed by such powers.

Months before the standoff over chemical weapons and the US threats to strike Syria and punish the regime for allegedly using them, US President Barack Obama drew a red line he said his country would not allow Assad to cross. But when the line was crossed (and here I’m neither claiming nor denying that the regime used chemical weapons), Obama dealt with the situation like an amateur: He warned and warned and warned until he provoked all of Syria’s allies. A good example of a strike (although I oppose one) are the airstrikes by Israel months ago. There was no word, no threats — only pure action. The case isn’t that the US fears striking Syria, but rather that it prefers not to pay a price that surpasses Syria’s value from the American point of view.

Probably Assad laughs all night when he’s watching the news. He’ll come across one rebel group fighting another in one area, and a regional power backing some groups verbally attacking another regional power. He knows that the West won’t lose anything if the opposition fails to topple him, as he is well aware that an end to his regime doesn’t mean an end to the war in Syria.

Ali Hashem is an Arab journalist serving as Al Mayadeen news network’s chief correspondent. Until March 2012, he was Al Jazeera’s war correspondent, and prior to that he was a senior journalist at the BBC. He has written for several Arab newspapers, including the Lebanese daily As Safir, the Egyptian dailies Al-Masry al-Youm and Aldostor, and the Jordanian daily Alghad. He has also contributed to The Guardian. On Twitter: @alihashem_tv